Začiatok stránky, titulka:

Pokračovanie obsahu:

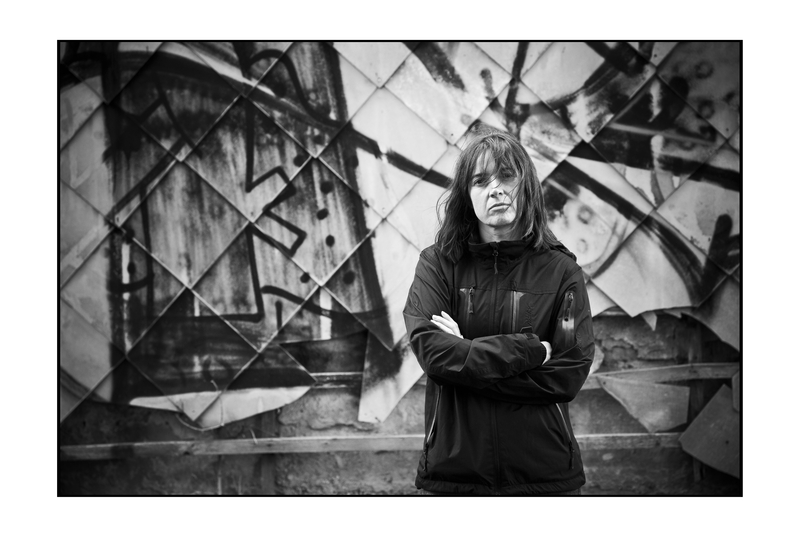

MARKO ŠKOP

I Can’t Run Away From Myself

After making or producing internationally successful documentaries (Other Worlds, Osadné), director Marko Škop made yet another début. His first feature film Eva Nová had its world première in September last year at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it won the FIPRESCI Award. The film was distributed in Slovak cinemas in November 2015. Škop has been living in Zagreb for several years where he has also managed to “settle down” as a filmmaker.

Where is your work concentrated now – in Croatia or Slovakia?

– In Slovakia, but I travel a lot to and fro.

Did it take you long to get into filmmaking in Croatia? What was your first project?

– The very first offer came from a festival organised by the Croatian-American producer, Branko Lustig. I led a workshop for foreign students; two short films were the outcome. Then I decided to learn Croatian. People are very keen on socialising in Zagreb, they go out together, there is a kafič – café on every corner. All my friends in Zagreb speak English, but the locals always switch back to their native language after a while. If I wanted to take part in the debate, I needed to speak Croatian. Our languages are similar, so it went smoothly and, of course, everyone appreciated my learning Croatian.

Did they know your documentaries?

– The Croatian ZagrebDox and Kosovan Prizren are the largest documentary film festivals in the Balkans. I was a member of the Jury in Prizren and Osadné was the opening film of ZagrebDox. The networking was very natural.

In Croatia, you worked on the TV series In Treatment which is known in our country as Terapia. How did you get into this project? It was made for HBO in the Czech Republic; how was it with the Croatian version?

– The public service TV made it in Croatia. My wife was involved in the project as one of the producers and she brought me into the discussions when she needed help with casting. The TV management was satisfied with my work and they offered me the job of second director. My Croatian colleague Tomica Rukavina directed 27 episodes, I directed 18. New faces appeared in the series together with Croatia’s biggest stars, such as Ana Karič, Goran Bogdan, Nina Violič and Elvis Bošnjak. It was a lovely job and a good school for working with the actors.

Many renowned filmmakers work for television,

for instance for the already mentioned HBO, where they get the chance to make high-quality films, TV series that are almost comparable with cinema films, wherein they have greater creative freedom. Several of them have almost become cult films or series. How do you, as a filmmaker, view television films?

– I’m involved in the development of two TV films that might get to be made in the coming years. In Croatia, it’s a story of a forty-something divorcée who has to fight for every bit of happiness. In Slovakia, it’s a reconstruction of dramatic historical events. Negotiations are going on for both projects with regard to whether and how they might be made. We’ll see, maybe in a year or two I’ll be making television films again.

So, you don’t perceive working for TV as something that will make you give up some of your filmmaking artistic ambitions?

– Not at all. I consider it important that the work be meaningful, and that is what many television formats in documentary and feature films offer. For instance, I’d love to make a travelogue around the Croatian islands, about their specific, unique features, the differences between them. That’s a dream morsel for me and one that I might get to make. As for the word “ambition”, I really don’t like it, it’s so double-edged. I’ve met authors in my life who were transformed into walking ambitions, as if the success and they themselves had become more important than the actual testimony itself. This attitude does not radiate any positive energy.

You are in a position to compare the available funds and the audiences in Croatia with those in our country. How does it look like with state support and the interest of the audiences in domestic production?

– The Croatian Audiovisual Centre HAVC operates with a similar budget to that of the Slovak Audiovisual Fund. The country has approximately the same size of population and not quite so many cinemas. HAVC maintains a reasonable proportion between support for films successful with audiences and films for the demanding viewer, they have blockbusters, such as The Priest’s Children by Vinko Brešan and films successful at festivals – The High Sun by director Dalibor Matanič gained an award in Cannes last year. Croatian cinematography is intensely alive.

It is very difficult to make an exclusively domestic title – co-productions are often necessary. What is your experience so far? What are your priorities when looking for a co-producer?

– I consider natural co-productions to be the best, for instance, when you’re shooting in a different country due to specific unique locations. It is most convenient to make Slovak films with a smaller budget at home but, since a film costs a lot, money from a partner is very useful, for instance for post-production. Trust is a key factor in co-productions, hence I try to work with friends and people on a similar frequency.

You managed to build up a successful company

with your friends which still operates without major changes and it is a guarantee of quality. What do you now, after a few years, think about the decision to establish your own production company? And what is its place in the current Slovak media environment?

– Artileria is a company of authors of films. Our main initiative is to make films and each one of us does something else as well as working on joint projects. Ján Meliš and František Krähenbiel were a great support for me at one moment when I wanted to give up on Eva Nová because we didn’t receive support for the project in the development phase and I hit rock bottom. Along with Zuzana Liová, they persuaded

me to carry on struggling, and I am very grateful

to them for that. Film production is a complicated process and sometimes as a producer you are really ready to top yourself but, on the other hand, there’s always joy when you get great satisfaction from what you do. Even though it might sound pathetic, I was happy during the shooting of Eva Nová itself and I am honestly delighted with the film. I wanted to talk about the importance of conscious decisions in life.

I see many misunderstandings around me that are caused by the fact that we let many things take their own course, that people allow themselves to be led by what they are experiencing at the moment and

do not think about the consequences for others. Our mistakes have the greatest impact on our nearest and dearest, on our family. Harm and misunderstandings create tensions in relations that can accumulate

over the course of years. At the same time, I was interested in the theme of mental transferrals from parents to children. We not only replicate the physical appearance of our ancestors, but also their mentality, their behavioural patterns.

There is a scene in the film where Eva Nová tells her granddaughter at one moment: “You don’t have to repeat anything after me,” and the girl’s toy repeats the same thing exactly in a mechanical voice: “You don’t have to repeat anything after me.” You inserted a comic moment in the emotionally tense situation...

– Eva then comes to a halt, she is taken aback by the repeating toy and she says: “And still it is repeating...”, the toy again automatically repeats after her and we look at the granddaughter and wonder if she’ll be just like her grandmother. I’m convinced that in many aspects she will be.

A certain auteur’s gesture is linked to your previous films. How is it in the case of Eva Nová?

– With each film I try to create something new, to touch upon something else, but I will always be present somehow. We cannot run away from ourselves, this is what Eva Nová is also about.

Your previous documentaries Other Worlds (Iné svety) and Osadné (Osadné) were linked with the Šariš Region, or with the north-eastern border of Slovakia, even though the problems of other regions surfaced through these films too. Are these regions still close and equally attractive to you from the documentary filmmaker’s perspective? Do you see other burning issues in them that you are continually thinking about?

– I’ll always be interested in the theme of the local in the global and equally in Eastern Slovakia. Half of Eva Nová was shot in Eastern Slovakia – in Pečovská Nová Ves and in several towns – Lipany, Prešov and Sabinov. We lived in a hotel in Sabinov that used to have a cinema. My parents used to go to this cinema. The Shop on Main Street (journalist’s note: winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film made by directors Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos) was made several decades ago in Sabinov, people still remember the shooting of the film with Jozef Kroner and the town gave us a big welcome. Mr. Baňas, mayor of Pečovská Nová Ves, created a completely homely atmosphere for us. Local people were cast as extras, actors from Prešov appeared in several roles. Even though Eva Nová could have taken place anywhere in Slovakia, we made the film in the country of my childhood where I feel very good.

Within this small area, in some cases Slovak cinema is paying the price for the unwillingness to collaborate (with the exception of the generation of documentary filmmakers that you belong to and who collaborate closely, help each other). What do you think about the Slovak film environment after all those years, all those films, achievements and, what is most important, from a certain distance as you live abroad?

– Every environment is created by individuals and

it is a reflection of specific people. Of course, it is most affected by those who have the power to make decisions. There will always be a conflict of interests; that is how it is, all over the world, not just in Croatia, but also in France which is a well-developed film country. The situation has certainly improved considerably in our country thanks to the Slovak Audiovisual Fund and the Radio and Television of Slovakia. I regard it as right to allocate the largest possible space to quality, whether it be a high- quality audience film or a high-quality auteur film. But it seems that, in our country, whatever previous film the author might have made counts for nothing, i.e. in determining the author’s potential for further results, good or bad.

That means that previous successful films don’t guarantee anything?

– It’s a shame because a great deal of energy is discarded along the way.

Documentary filmmakers who have decided to make feature films, claim that greater freedom is one of the reasons why they did so. Was that your case also?

– Every author has internal themes that he/she is interested in and looks for ways of depicting them as effectively as possible. I decided on a feature film in the case of Eva Nová because of the possibility to dig deep in the depiction of tense unresolved relations. Of course, the same can be achieved in documentary film but the immersion in the intimacy of a family with generational transferrals involves all the characters present, even small children; if I’d had real people, I would have come up against limits, my own human limits. I definitely felt more free with a feature film, but the converse might be true for the next theme and a documentary would be the appropriate means of allowing me to say things the right way.

The film had its world première at the Toronto Film Festival. How did viewers react to Eva Nová? And how did you enjoy the festival?

– The North American audience experiences films a bit differently from the European one. In Toronto, people expressed themselves out loud, you could feel it in the air when they rooted for Eva Nová or they murmured no, don’t do that! I was a bit taken aback as the account is quite hard. On the other hand, it served to indicate to me that the viewers were able to identify themselves with the characters. Even after the discussion had finished, many people still came up to share their experiences with me in person.

Marko Škop (1974, Prešov)

He studied journalism at the Philosophical Faculty of Comenius University and documentary filmmaking at the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava. Together with director Juraj Johanides, he made the mid-length documentary Celebration of a Lonely Palm (Slávnosť osamelej palmy, 2005); immediately afterwards on his own he directed the full-length documentary Other Worlds (Iné svety, 2006) for which he received, for instance, the Audience Award and the Special Mention at the Karlovy Vary IFF and the Talent Dove at the DOK Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Films. In 2009, he made the documentary Osadné which won the Best Documentary Award at the Karlovy Vary IFF.

Mariana Jaremková

PHOTO: Miro Nôta

Digitisation Has a Multi-level Significance

Many experts with a variety of special project. Mária Ferenčuhová, Eva Filová, Petra Hanáková and Eva Šošková collaborated in the project as film historians – curators. In the following interview they clarify their respective involvement in the project but they mainly discuss the outcome of the digitisation of the audiovisual heritage for film experts, filmmakers, historians and the viewing public.

Eva Filová, PHOTO: Miro Nôta

How did your work as film historians – curators fit within the Digital Audiovision project and what are its outputs?

– Mária Ferenčuhová: I was the first one to get involved in the project in November 2012 when discussions were held in the Slovak Film Institute as to which of the plethora of short documentaries should be digitised. My original ambition was to watch all the available films without any exceptions and to choose those that reflect the period “film operation”, with films made to order, with works that were schematic, conformist, and, of course, those that were innovative for their period in terms of theme or form. However, that was not a task for one person and so Eva Filová and Petra Hanáková became involved in the project. The three of us then divided the films by theme. At the same time, Eva Šošková joined us. She had already dealt with animated film in her doctoral research. Paradoxically, due to lack of time, I left the project shortly afterwards. The outputs of my research were mainly scientific studies that were published in Kino-Ikon, others in turn in the monographs Film and History 4 (Film a dějiny 4) and Documentary Film in V4 Countries (Dokumentárny film v krajinách V4). Among other things, in my outputs I tried to note how the opinion of Slovak short documentaries changed in the individual periods. Eva Filová then chose films with a similar mind-set that were screened in Cinema Lumière. She was the one who selected the basic themes which showed the different ways in which short films were made and produced in comparison with full-length feature films.

– Eva Filová: I worked on a separate systematic research which consisted of several components. First the area to be examined had to be chosen

– I opted for a big package of non-fiction films with the theme of the Slovak National Uprising which were mostly made to political order in the Short Film Studio in 1945 – 1989 and which quite naturally moved away from the centre of interest after the change of regime. This entailed more than a hundred films which, from a total production of 3,300 films, is no negligible number. After a time it became necessary to

look at them from a different perspective, not just the ideological one. To my surprise, many of them would pass even today as an exceptional testimony of the given period, an interesting investigation of tragic events or an inventive handling of archive materials. It was necessary to watch all the films thoroughly, to take notes, to check and possibly make their original annotations more accurate, to write down the key words, to search for an adequate, representative still and a film extract approximately one-minute-long. During this initial work extending over several months, I started placing the processed films into the emerging categories and to write a study that gradually developed, until

it turned into four consecutive parts in Kino-Ikon. As the research was started in the year

of the 70th anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising, further activities outside of the project were spontaneously added: a selection of the

ten best documentaries for .týždeň magazine, the August block of films in Cinema Lumière within the Shorts from the Archive series, the selection and matching of short films screened prior to full-length films for the entire August Filmotheque of Cinema Lumière, a block of short films for the Brno 16 Festival. I presented the last selection of films with the characteristic title “The International Nature of the Slovak National Uprising” in summer 2015 to the foreign students of the Summer School of Slovak Language and Culture at the Philosophical Faculty of Comenius University.

– Petra Hanáková: My job was to perform background research: to watch, analyse

and describe the films, to pick out their “substitutional” fragments and static shots, to create collections and reference notions, partly also to choose films for digitisation. Originally,

I was supposed to deal mainly with Nástup (i.e. the beginning of newsreels) and – as I am also an art historian – with film on art, but eventually I got “sucked up” by the work and it moved me in another direction also. The collections of the SFI’s archive are unusually rich – what we are familiar with is just the tip of the iceberg, especially in the documentary film segment. If

I may take the liberty to answer the question of “outcomes” with a single word, then I will say: knowledge. It was a unique opportunity to get to know and to examine films that were up to then unknown, and to subsequently mediate them,

for instance in the texts that I am writing now and publishing for Nástup (newsreels during the First Slovak Republic), in the introductions to screenings for the 4 Elements Film Seminar or while programming the films for the Fluid Muse exhibition where, thanks to my working for both institutions, I naturally linked the collaboration between the SFI and the Slovak National Gallery.

– Eva Šošková: I dealt with animated film in the project and my main job consisted of several steps. I received the list of films to be digitised and I wrote a protocol for every film I watched. I recorded the key words based on the theme and characters, I wrote down the genre, the use of speech, the animation technique, for whom the film was intended, etc. I evaluated the protocol and collated blocks of films with a common theme, I created film profiles of the filmmakers and specified who the film was intended for. Such blocks of films could, for instance, be part of retrospectives at film festivals. An extensive study capturing the periodisation of the history of animated film, the extent of auteurship of the films and an analysis of the film styles, the work of the filmmakers with the theme and genre, and a quantitative evaluation of the animation techniques, constituted the verbal evaluation of the research using the protocols.

Eva Šošková, PHOTO: Miro Nôta

How will the digitisation project affect work with film archives and what could be its greatest impact for film historians on the one hand, and filmmakers on the other?

– Mária Ferenčuhová: In my view, a readily available and compendious database plays a key role. When the SK CINEMA film portal was put into operation, this made it possible to comfortably search for films based on various keys. Hence, it is the first contact with the film archive, even though historians and filmmakers approach the archives quite differently. Filmmakers are often looking for a specific type of shot, a specific historical figure or a recording of a specific event, many times purely as an illustration. Film historians mostly approach an archive with regard to the issue examined, with expectations or hypotheses which they check by means of film. They do not look for a specific type of shot, they seek what materials were made on the given theme. And the historians who deal with political history approach the archives quite differently. SK CINEMA is a useful tool for all these types of searches or research.

– Eva Filová: For a historian, it is important

to have the broadest possible field of vision unveiled. Because working with a limited

amount of material might lead to a misleading generalisation, to the repetition of the same titles and the same names. I consider digitisation to be not just a useful restoration of the cultural heritage, but especially the long-term process of making all available materials accessible

– documents, photographs, complete films or their parts, film posters and magazines. A lot

of information can be found even now in the SFI databases via the SK CINEMA portal. If I deal with a filmmaker, I am glad to be able to locate the available relevant and verified materials, not simply those on “Wikipedia”. Digitisation represents a certain satisfaction for a filmmaker, that due attention is paid to his film and that it was not just abandoned somewhere in a box.

– Eva Šošková: The basic property of digitised data is their capacity to be disseminated and then their accessibility. Accordingly, digitised audiovisual materials are destined to get readily to the people who are interested in them. Making less familiar and unknown films accessible will broaden the exploring horizons to historians,

and for filmmakers digitisation will technically simplify the use of archive materials in their films.

Mária Ferenčuhová, PHOTO: archive of M. Ferenčuhová

Can digitisation support interdisciplinary work with film in the areas of art and science? Will

a film recording for instance become a more frequently used source for historians?

– Mária Ferenčuhová: Relations between institutional historiography and film have been

my favourite topic for a long time now, so I will answer this part of the question especially. Unlike, for instance, German historians who have been “discovering” film sources gradually from the 1950s onwards, through the French and Anglo Saxon historians who joined them by the end of

the 1960s, the Slovak ones have until recently almost hardly ever worked with film sources at

all. Only in the last decade, mainly thanks to the younger generation of historians and thanks to

the orientation of research towards the history of representations and cultural memory, works based on the analysis of film sources have also started to emerge. Digitisation will simplify the work for these historians considerably. The intermediary nature of curator work in the Slovak National Gallery in recent years also demonstrates that intersections of film with other forms of art are attractive and carry a lot of information.

– Eva Filová: Definitely, a connection between film, film history and social sciences is missing here. It could, for instance, be beneficial for a political scientist examining normalisation to see how Husák’s status as a key figure of the Slovak National Uprising was strengthened in the period non-fiction production. We encounter film in museums and galleries more frequently.

– Petra Hanáková: Definitely yes. This way

film is more available for use. Thanks to the SK CINEMA databases, which are older than the Digital Audiovision project itself, nevertheless, thanks to the project they are also copiously filled with data, it is possible to work with films “more operatively”. Thus, the researcher (from any discipline) sees and can readily search for what is available in the funds and in what form. I hope it will help because, in my view, historians in particular work with audiovisual material and its analysis disconcertingly little. Today, interest in the Slovak State is booming but which historian has ever watched the period newsreels?

– Eva Šošková: That is related to how accessible it is, so it could be. However, everything depends on its systematisation and whether some data will be made accessible electronically.

Petra Hanáková, PHOTO: Cinema Lumiere

What in your view are the benefits of DA for the general public, what possibilities are opening up in this respect and how could they be used?

– Mária Ferenčuhová: Thanks to digitisation the Slovak public can, for instance, finally discover the less prominent treasures of Slovak cinema, such as short films.

– Eva Filová: I hope that digitised materials will just be made more widely accessible. Not only in the form of projections in digitised cinemas and DVDs and Blu-ray Discs issued, but mainly via the Internet: thematic collections, interesting “stories” of films and virtual exhibitions of photographs and posters.

– Petra Hanáková: At the level of hardware aesthetics – because it was mainly full-length feature films that underwent the “big digitisation”, i.e. not only transcription but also a comprehensive restoration – our films will be “cleaner” and “more colourful”, it will be easier to distribute them in cinemas (that are also gradually being digitised thanks to support from the Slovak Audiovisual Fund). Therefore, they will (hopefully!) be a more solid and present part of our cultural awareness

– Eva Šošková: As for the general public, I see the importance mainly in the provision of films for retrospectives at festivals and the further dissemination of audiovisual material by means of interesting DVD compilations (in the case of short films).

Can digitisation make it easier for foreign film experts to gain access to our film archives and thus stimulate their interest in our cinematography?

– Mária Ferenčuhová: That essentially depends on whether the databases but also the materials made accessible will be, so to speak, “foreign-user- friendly”. The SK CINEMA film portal does not yet have an English version. However, curator outputs can have it more easily and their availability on the web can clearly arouse such interest.

– Petra Hanáková: Here again I consider www.skcinema.sk to be the best gateway but, of course, also the publication of restored/digitised works on structured (i.e. with bonuses and several language versions) and “fictitious” DVDs, but maybe finally also curator work with an “on demand” format.

– Eva Šošková: It can, but everything again depends on the systematisation of this material and the access of foreign experts to it, for instance without needing to physically visit the archive.

Mariana Jaremková