Začiatok stránky, titulka:

Pokračovanie obsahu:

This Is the Year of Hanák, Havetta and Jakubisko

The directors Dušan Hanák, Juraj Jakubisko and Elo Havetta are among the most signicant filmmakers of Slovak cinema. They all studied at the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU) in Prague and all were born in the same year – 1938. Hence, this year marks their 80th birthday. However, Havetta only managed to make two full-length feature films before he died prematurely.

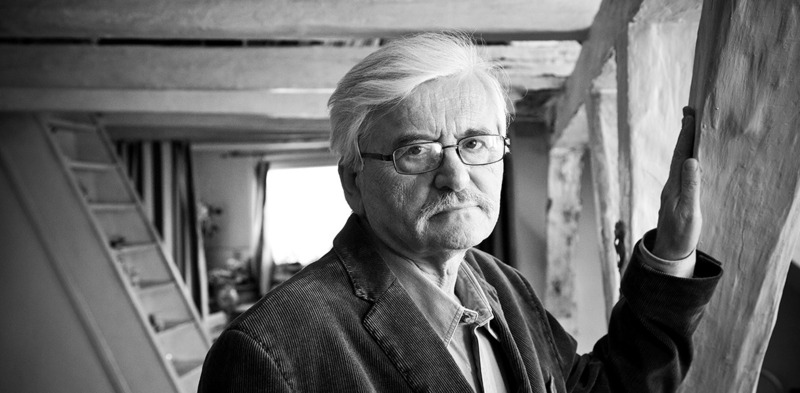

DUŠAN HANÁK

His last film Paper Heads (Papierové hlavy, 1995) frequently uses the term “to purge”. That is because it is a documentary about life under the totalitarian regime. Socialism tolerated only a grey mass which it hypnotised with slogans about brighter tomorrows and tried to break, even by force, those who protested or who had a problem in adapting. And the violence applied was often brutal. Dušan Hanák talks about all that in his film made six years after the fall of the Iron Curtain. In the film he brings into stark contrast the slogans of the regime and the sad testimonies of its tormented victims.

Hanák himself was confronted with bans during his film career. Also because he often made films about people from the periphery or about an ordinary man who lived his everyday life with all his desires, trials, tribulations and failings flashing through his life. The regime did not imagine exemplary film heroes, prospering within the safe arms of the socialist society, in this way. Instead, Hanák portrayed old people from remote corners of Slovakia who were imbued with a totally different type of beauty – the authentic inner beauty of a sorely tried but free man as depicted in the much-awarded full-length documentary Pictures of the Old World (Obrazy starého sveta, 1972). Rosy Dreams (Ružové sny, 1976), in turn, tells the poetic story of the young village postman Jakub who falls in love with the gypsy, Jolanka, but their naïve ideas of cohabitation have ultimately to be abandoned. In I Love, You Love (Ja milujem, ty miluješ, 1980) he moves among the community of railway workers and focuses on the sad-funny chracter of a bachelor looking for a partner and drowning his sorrows in order to boost his mood and courage to live a life which he doesn’t want to lose. Hanák was awarded with the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1989 for this film.

Dušan Hanák studied at FAMU in Prague and, prior to making his full-length début 322 (1969), he made several short documentaries (e.g. Artists/Artisti, Learning/Učenie, Old Shatterhand Came to See Us/Prišiel k nám Old Shatterhand, The Mass/Omša) which attracted international acclaim. In addition to the aforementioned full-length feature films, he also made Simple Pleasures (Tichá radosť, 1985) and Private Lives (Súkromné životy, 1990).

— text: Daniel Bernát —

photo: Miro Nôta —

ELO HAVETTA

He started making feature films at the age of 31; he made two full-length films (Celebration in the Botanical Garden/Slávnosť v botanickej záhrade, Wild Lilies/Ľalie poľné), several student films, he collaborated in the making of TV magazines. He died at the age of 37; however, he inherently belongs to the generation that changed the face of Slovak film. They introduced themselves along with Juraj Jakubisko, and the public started to perceive them as twins who wanted to make films differently from their predecessors. Both graduated from the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (UMPRUM) and the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), they had a love of photography in common, they collaborated with Alfréd Radok, they presented themselves to the public at almost the same time. In the 1960s, the period was ripe for film to seek out other paths in Slovakia also. The management constellation in Slovak Film was also conducive. Jakubisko, Havetta, Lubor Dohnal, Hanák, Igor Luther and several others proclaimed their programme. “Uher, Barabáš, Solan and Hollý strove to make engaged socially-critically focused works. However, the young generation display their buffoonery, their individual view of the world as they are loath to bear any responsibility for the profane concepts: world development, nicer future,” stated Lubor Dohnal.

I had the opportunity to bring this generation to the world on the pages of newspapers. Juraj Jakubisko, the reader of his colourful dreams, Elo Havetta, the more silent introvert who encrypted his dreams in numerous silences and insinuations. The sceptical interpreter of life, Dušan Hanák, was the third distinctive personality of this generation.

In a more communicative moment, Havetta confessed to being closer to Chytilová than to Forman, but in his beginnings (Forecast: Zero/Předpověď: nula and 34 Days of Absolute Calm/34 dnů absolutního klidu) he was influenced by Schorm. At this time, every representative of this generation was searching for his own language: “Havetta is the Brueghel of Slovak film, Jakubisko is the Bosch,” was the way in which Václav Macek characterised them.

After a short favourable period came setbacks in the 1970s – Havetta was beset by problems and insecurities, he shut himself away and was depressed by the obstacles he constantly found under his feet. In 1973 to 1975 he collaborated stimulatingly with the TV company on the magazines Swallow (Lastovička) and Come In (Ráčte vstúpiť!), but on 3 February 1975 his work and his life’s journey were closed forever.

— text: Richard Blech —

photo: archive of the SFI —

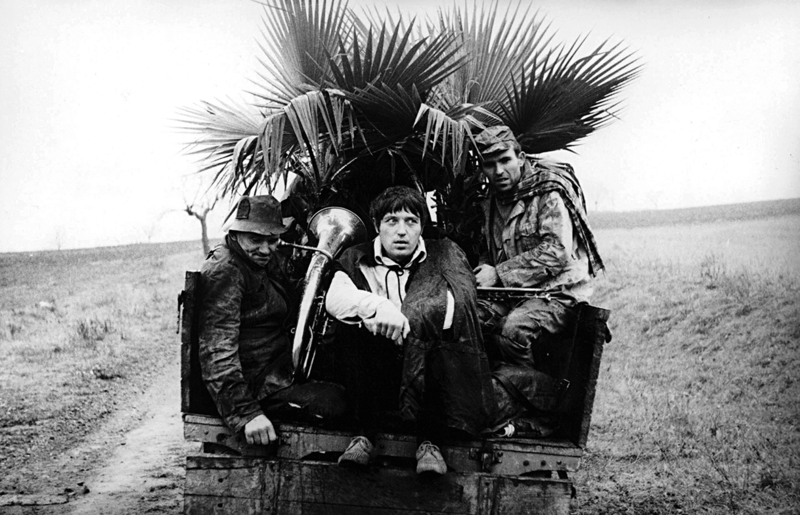

JURAJ JAKUBISKO

The young generation of Slovak filmmakers came into cinema in an impressive manner in the late 1960s. Their débuts spelled out a future filled with promise and yet, at the same time, they were mature films. Actually, so mature that they can still be considered as breakthrough films even after so many years.

Jakubisko was the first member of the young generation to make his début with the film The Prime of Life (Kristove roky, 1967). The fi lm about the painter Juraj (it is no coincidence that the protagonist bears the same name as the director) attracted interest with its story and also with the way in which it was narrated. Juraj is not burdened by the past, he does not concern himself about the future, the present alone is important to him. His life is reminiscent of a game without rules and this sort of life attitude resonated with the majority of Jakubisko’s generation. After The Prime of Life he made several films in quick succession: Deserters and Pilgrims (Zbehovia a pútnici, 1968), Birdies, Orphans and Fools (Vtáčkovia, siroty a blázni 1969) and also See You in Hell, My Friends (Dovidenia v pekle, priatelia) which, unfortunately, he was only permitted to complete in 1990.

His impressive start, however, was not allowed to continue in such a fascinating manner, as for years the strengthening normalisation period did not afford adequate opportunities to Jakubisko. Many of his colleagues emigrated or were banned from filmmaking and, just to make certain, Jakubisko was moved to short fi lm. It was a cruel punishment and he was only partially pardoned by the establishment in 1979 when he was allowed to make the film Build a House, Plant a Tree (Postav dom, zasaď strom). Unfortunately, his work was again repressed as a result of this fi lm as the normalisation leaders decoded his film version of socialism as an image of theft eternally repeated. This film was followed by Infidelity in a Slovak Way (Nevera po slovensky) and in 1983 The Millennial Bee (Tisícročná včela), extremely popular with audiences, received its première. It is actually Jakubisko’s and writer Jaroš’s contribution to the history of magical realism and the author managed to develop this specific poetics, based on mingling the real with the surreal, mainly in the fairy-tales Lady Winter (Perinbaba, 1985) and Freckled Max and the Ghosts (Pehavý Max a strašidlá, 1987). However, poetics also found good use in Ambiguous Report on the End of the World (Nejasná zpráva o konci světa, 1997). In addition, Jakubisko likes to make stories taking place on the border between history and fiction, as confirmed by the films Sitting on a Branch, I Am Fine (Sedím na konári a je mi dobre, 1989), It’s Better to Be Rich and Healthy Than Poor and Sick (Lepšie byť bohatý a zdravý ako chudobný a chorý, 1992) or his most recent film to date, Bathory (2008).

— text: Peter Michalovič —

photo: archive of the SFI —